In February I told you about my season of harvest, of healing, of opening up. That season was short. Another season of difficulty followed.

It has been a hard spring. I had a frightening ordeal with housing insecurity which consumed much of the past two months. My initiative to bring Squirrel Dialogues into the Evergreen Changemaker Lab sputtered, stalled, and collapsed. My Patreon income has dropped and my living expenses have increased. My writing and video work also came to a halt (my most recent Squirrel video is below).

In all this I have felt totally alone. I want to be precise with my language here: I *felt* alone. And I’ve realized this is the essence of my trauma. A deeply ingrained felt sense of aloneness which I’ve traced back to babyhood.

I wonder how many of you feel that way. I’ve learned to see it and hear it in others. It looks like eyes that don’t smile. It sounds like a worldview devoid of magic, life, and love. It looks like so much of the human-built world. I wonder if this aloneness is endemic. I wonder if this aloneness is at the heart of our sense of disconnection.

I’m taking an MIT online course called the U-Lab. The lead professor of the course, Otto Scharmer, talks about the poly crisis: Disconnection from self, disconnection from each other, and disconnection from nature. I wonder how much of this disconnection is inculcated in us in our earliest weeks. An inheritance tracing back to the bandit centuries of medieval Europe, to the reaping of America’s forests and peoples, to the theft of brown bodies from humanity’s very cradle. Also known as “intergenerational trauma.”

I said I felt alone in all this. The truth is I was not alone. Am not alone. This spring friends and strangers in Olympia helped me find housing. And dear ones held me in my suffering. And on occasion, I held them.

In my attempt to repair with my parents, I told them that as a child, what I needed most was to be held. And they told me, Evan, we did hold you. And it is true, I was physically held as a child. But what I am talking about is bigger than that. I’m talking about being held in your truth. Being held in your weakness, in your smallness, in your fear, in your anger, in your grief, in your joy, in your wonder, in your silliness.

And I now know it was impossible for them to hold me in my truth. Because the truth was that my father was overwhelming to me, frightening, unsafe, harmful. And I now know that abuse and neglect happen in the shadows. Yes, in the dark confines of family homes and intimate relationships, but also in the shadow psyches of those who cause harm. Those unseen parts, plain to others but invisible to their host. Because no one in their fullness would choose to harm another.

So it was precisely when I needed my parents the most, when I was being abused and neglected by them, that they were not able to hold me. And the essence of childhood trauma is the unheld child. Because children are resilient when paired with a safe adult. With someone who can really hold them.

In the past year I have learned what it feels like to really be held, capital H held. And I’m learning how to hold others. And when holding is happening, my soul is content, the terrified child in me quiets. There’s nowhere I’d rather be.

Here are four vignettes on the theme of holding.

Held Four Ways

1 - In the ketamine

I recently resumed self-guided ketamine treatment for my complex PTSD. Most of my medicine work has been solo work. But in recent years I’ve heard the increasingly loud message—often in the midst of the medicine--that I must stop doing this healing work alone. That if I was wounded by people, I need to heal with them.

And so I finally asked for help. I asked a friend to sit with me. I told him all he’d need to do was hold my hand. I told him I’d probably lay down quietly for an hour while the medicine worked through me.

That is not what happened.

Instead, my traumatized child came forth, shaking, crying, and grappling, in child language, with his abandonment and abuse. Luckily my friend had the attunement, and the experience of healing spaces, to know what to do. Or better yet, how to be.

In grief work, elder Laurence Cole talks about “permissionary” culture. In that we allow whatever needs to come forth, to come forth.

So my friend held my body and allowed my anger, my story, my grief to come forth.

I’m so mad, I said through chattering teeth.

My mommy and daddy didn’t love me.

No one caught me.

It came through like a torrent and my friend had the sense to step aside and let it pass. But he never let go. And in the medicine I could feel the shift. From suffering alone to suffering with. My child noticing that there was a safe man holding us tight. A very old story being rewritten.

In the midst of this I asked him, ever worried about taking space, Is this alright? And he said, I have capacity. And something frozen in me melted. Never had my child heard those words.

2 - At Mount Tahoma

In the wooded foothills of Tahoma (Mt. Rainier), I took my child and myself to a grief ritual.

Some 30 of us crowded into a yurt, where our guides Ahlay Blakely and Laurence Cole held space. And Ahlay made a radical invitation. She said, Ask for what you need. Use this space, use us.

And she demonstrated with some volunteers. She sat down on the floor and invited someone to sit in her lap and lean against her chest. Then she called in another volunteer who sat against Ahlay’s back, forming a human backrest. And I thought, We can do that?

One of the main pillars of community grief work is the idea that we each have our personal encounter with grief. In grief rituals we allow each other that encounter. We let people cry and rage. We don’t interrupt, we don’t make it better, we don’t offer a tissue.

But then there’s the other pillar, named by Ahlay—Ask for what you need. Maybe you need to grieve in the arms of another. Maybe you need to speak your truth as someone holds your eyes with theirs.

And then there’s a third, subtle pillar. Use your intuition. Sometimes someone needs you, but can’t speak it. Sometimes you offer yourself.

So when we began singing and drumming at the launch of the ritual, I took Ahlay’s advice to heart. I systematically asked for what I needed. I wanted a dad to cry on. I turned to a big bear of a man, someone I’d just met, and asked him if he’d hold me like a dad. And he said yes, as if this was a normal request.

We walked into the ritual space and I leaned back on his big body and my child came forth and wept. He wrapped his arms around me and held me silently, gentle as an old tree.

Then I shifted my body and looked at him in the face and we looked at one another frankly for a long moment. His eyes were soft. Remember this, I told my child.

Then I asked a big bear of a momma to hold me, and I wept into her big body. And I asked her to talk to me like a momma, and she cooed, O sweet darling… And I dampened her shirt with my tears.

Then I asked two people to hold me as parents, and they did, two caring beings caressing my face as I shook and sobbed.

And then, near the end of the ritual, I sensed that one of my helpers would need help. And sure enough she walked into the ritual space, and I followed her, I was her witness. And I beheld her as she walked to the rage station and punched a pillow. Not as a woman, but weakly, half-heartedly, like a little girl.

And then she shuffled over to the grief altar, sat on her knees, child-like, and wept softly.

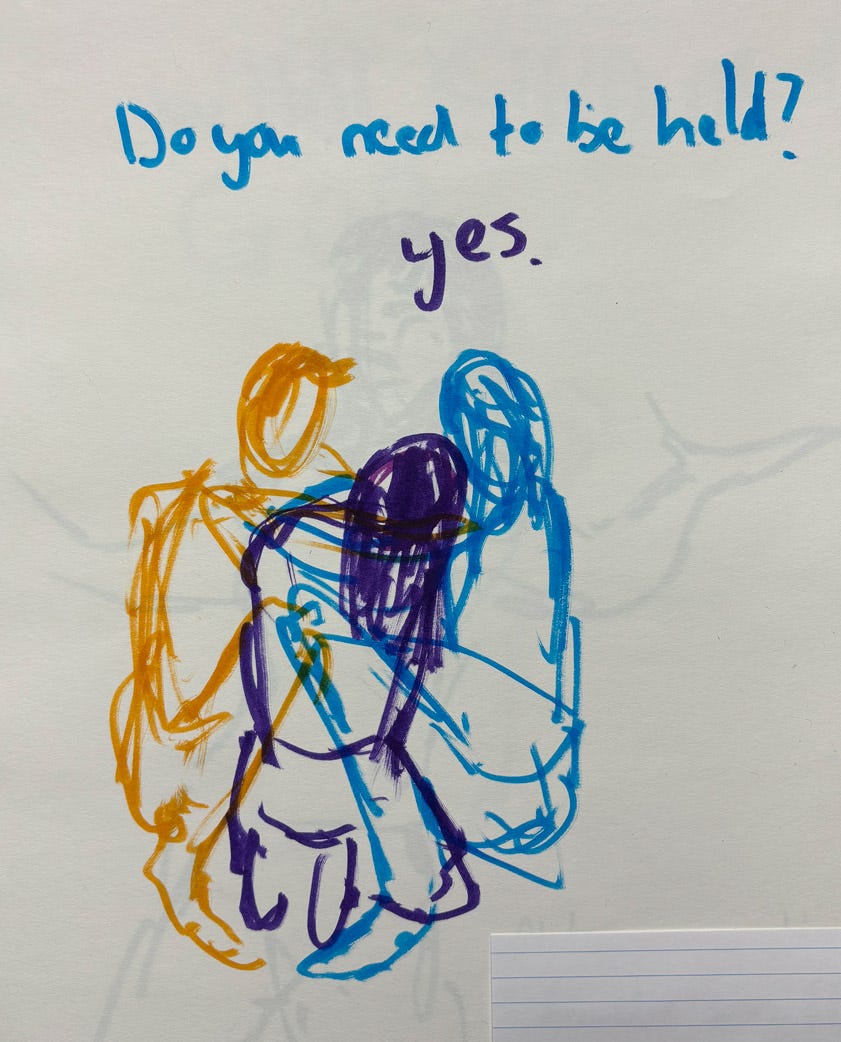

And I stood over her not wanting to interfere. But sensing that this was a lonely child’s grief. And that lonely children need to be held. So I crouched next to her and spoke into her ear: Do you need to be held? And in the tiniest voice, she said, Yes.

As she leaned into my body, I made a signal and another helper came over, and we held her until the drumming and singing stopped, until the end of the ritual.

3 - My Dear One

On spring break I went to visit a loved one who was in the throes of a painful ordeal. And I carried the single-minded purpose—I would hold them.

I was following my intuition, something in the sound of their voice on the phone, echoes of that lonely, overwhelmed child.

And finally the moment came, when in a private moment with me, their anger came to the surface. My old self would have run, or appeased, anything to get free of their anger. But instead I sat with them, and looked them frankly in the eye as their anger came through. And I had the sense to step aside and allow it.

And then their energy shifted, and they began to shake, and I said: Come with me. And I leaned back on a couch and invited them into my arms and I held them as their anger, their grief, their shame came rolling through. I held on tight. I said, Yes.

They asked, ever mindful of taking up space, Do you need to go?

And I said, Don’t worry about the time. I have capacity.

An hour passed. Maybe two.

And part of me was watching this all with awe. Because I didn’t used to be this strong. And though I was soaked with my friend’s tears, my heart was glad. There was nowhere else I’d rather be, nothing else I’d rather be doing.

4 - On Suquamish Land

At a men’s grief ritual this weekend I showed the men what Ahlay had shown me—that we can hold each other in so many ways.

And another big bear of a friend held me as my child let out the pain of the past months, and the past lifetime.

And afterwards, I sat in a cuddle pile with my bear friend and another kind-eyed man. And my friend said, I felt so powerful when I held you. Grounded, warm, and strong.

And the kind-eyed man said, Strength has been coming up for me, like a mantra. Then he asked, What’s your word?

And I tried to speak but another wave of emotion came through, and I wept, somewhere between grief and gratitude. And he laughed and said, Sometimes it’s ugly-crying.

And finally I gasped: Reunion. Homecoming.

As the drumming softened and the ritual waned, I danced, in celebration. And I circled by a man weeping in a chair and felt a tug in my heart: Lonely child energy. And I circled by again and crouched next to him, and asked: Do you need to be held? And in a tiny voice, this strapping broad-shouldered man said, Yes.

And it was my turn to hold, and I held him tight as he cried. And Old Me would have worried, What if he doesn’t stop? But New Me held a knowing: He’ll stop if you hold him long enough.

He cried and cried, in waves, as the drumming slowed and ceased, marking the closing of the ritual. Still he cried. And so in the quiet I began to sing:

I reach down, down, down deep

I reach down, down, down deep

Mother Earth welcomes me

Mother Earth welcomes me

And then he, too, fell silent. And we men lay there, holding one another, gentle as old trees.

##

Song by Alillia Johnson via my friend and touch activist Aaron Johnson

Links

Peter Levine, founder of somatic experiencing, discusses his new autobiographical book about trauma, on Being Well.

So tender dear Evan, so real. Thank you for sharing this. Thank you for holding others and letting yourself be held. <3

Thank you for being you, for doing this deep world changing work, and for bringing back and sharing such medicine in your writing with such eloquence, poetic skilfulness, and fierce vulnerability. ❤️